“It’s what happens when Canada is run by a Prime Minister indistinguishable from a 17-year-old social justice warrior with an Instagram account.”

Terry Glavin tells Peter Stockland how disastrous reporting by the nation’s media created social panic, despair and reputational chaos

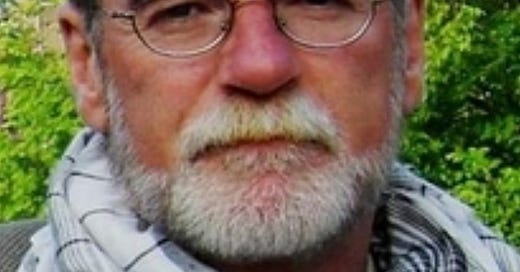

(Editor’s note: This is the first of a two-part series based on an interview with Terry Glavin, author of The Year of the graves: how the world’s media got it wrong on residential school graves. Part Two will be posted later this week and Peter Menzies’s regular Monday column will resume next week)

On June 4, 2021, I ask…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Rewrite to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.