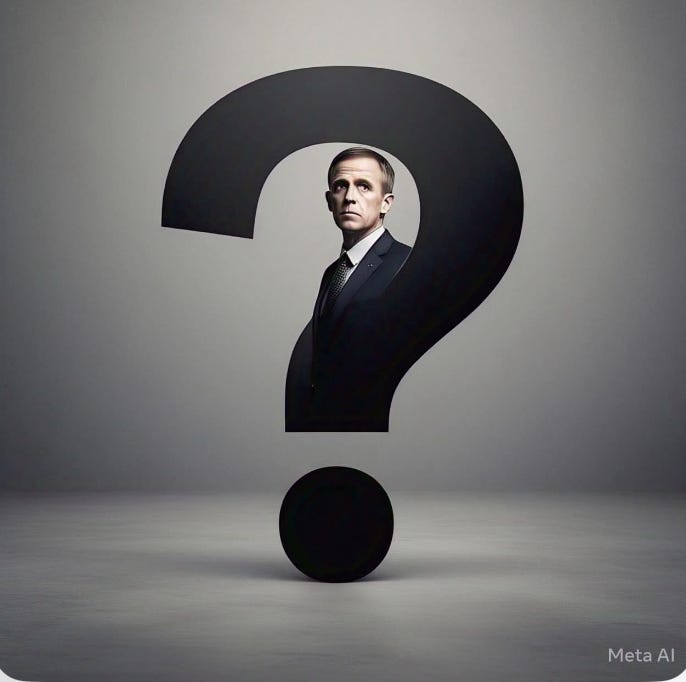

We know the resume but media have yet to inquire into the character of the man who would rule Canada

The resume looks great, but no one should get hired without answering challenging questions in an interview. That's the job of journalists.

Former Editor-in-Chief of the Montreal Gazette and Rewrite contributor Peter Stockland takes a look at the media’s scrubbing of Liberal leader Mark Carney

In a recent scrum, Liberal leader Mark Carney swerved away from a question about plagiarism in his doctoral dissertation by expressing ironic satisfaction there was interest in his long-ago academic career.

“I’m pleased there is such interest in a dissertation on game theory from 30 years ago,” he told an inquiring reporter.

The retort displayed one of the shrewdest uses of highly skilled disingenuousness in recent memory. It appears to have had the desired effect – in the scrum as well as on the campaign trail – of extinguishing a story that was struggling to catch fire anyway.

Yet the misdirection ploy itself should be the catalyst for awakening the sleepy-head journos currently following Carney, and transforming them into real news hounds pursuing the scent wafting from the plagiarism accusations.

For starters, nowhere in his dismissal does the Liberal leader actually deny that he did, indeed, plagiarize the numerous passages identified by National Post reporter Catherine Lévesque when she broke the story late in March.

He didn’t because he can’t. The side by side comparisons of the offending quotations, which Lévesque provided graphically with her story, makes such denial impossible. The clear, virtually exact replication of uncredited language belonging to others is self-evident. Whether they constitute actual academic misconduct remains a matter of debate. But it’s a debate this country’s professional journalists should be doing all in their power to foster.

They need not – should not – foster it with the intention of acting as judges of specific ivory tower jiggery-pokery, which the vast majority (“hi mom!”) have no credentials or competence to adjudicate anyway. Nor should it be done with surreptitious partisan intent: boosting another party leader by dragging, in this case, Carney down.

It should be done because it is the job of journalists to provide, without fear or favour, information essential to citizen conversation and democratic decision-making. It is their job at all times, but is especially critical during an election campaign. Plagiarism, with or without subsequent punishment, belongs to the highest order of that essential information.

Why? Because plagiarism is theft. It is the stealing of another’s intellectual property. Worse, it is the “cheap sin” form of theft because it steals what has already been publicly provided for the mere price of acknowledging credit. As such, as an issue, it goes beyond the shallow obsession with personality that infests and makes putrid our politics. Plagiarism is a crucial tell by which we discern personality from character.

We might like or dislike a certain party leader’s perceived aggressive, arrogant, one-man-band personality. But those are surface traits that various factors can amend: maturity, self-confidence, the weight of office, a punch in the mouth in a Texas roadhouse. But character goes beyond malleable habits and sinks deep into reflex, instinct: what one does when there isn’t even a compelling cause for it.

Just so, owning up to, say, plagiarism is a mark of character, though by its nature just confessing can’t erase the original failing. Deflecting it, misdirecting by pointing to the obscurity of the subject in which it occurred or the mists of time since it was committed, is a mark of something Canadian voters should be equipped to assess very, very seriously.

Plagiarism itself is, as noted, a very serious matter. Journalists, on a par with academics, are the people in this country who must treat it most seriously of all. Their reputations, their livelihoods, in one case even a journalistic life, are at all times and everywhere under its shadow. If they ever forget that, they can remind themselves by saying out loud the name Ken Adachi.

In 1989, only seven years before Mark Carney submitted his now contentious dissertation, Adachi, 60, went home from being a book reviewer for the Toronto Star and committed suicide. According to the online source ABC Bookworld, among others, he was under investigation for a second plagiarism offence: lifting three unattributed paragraphs from Time magazine. He had been fired from the Star eight years earlier for plagiarism but was rehabilitated and allowed to practice his craft again.

Such an end is a horrendous tragedy that seems unthinkable for something like plagiarism. But it does testify to the seriousness of the wrong involved: it brought so much shame to Adachi that his life no longer seemed worth living.

No sane person would even hint that such a degree of shame should be inflicted on anyone, including a man seeking to be our prime minister. Neither, however, should this country’s journalists accept obvious deflection and misdirection on a matter that gives voters a vital indicator of the character of a would-be head of government.

What voters do with such an indicator, how they resolve its pros and cons for themselves, is self-evidently up to them. But members of a media complex that fails to supply in a fair, balanced, non-partisan, but relentless way, voters’ needs in that regard should ask themselves if they are guilty of being disingenuous just by showing up for work.

A tragic story that only amplifies in my mind that Mark Carney is an unworthy

candidate.

Plagiarism is like Blackface, it is not important if it happened long ago if you are a Liberal. Unlike long ago prior Conservative social values which must be trotted out now.